Added Sugars vs Natural: Is Natural Sugar Significantly More Healthy?

Summary

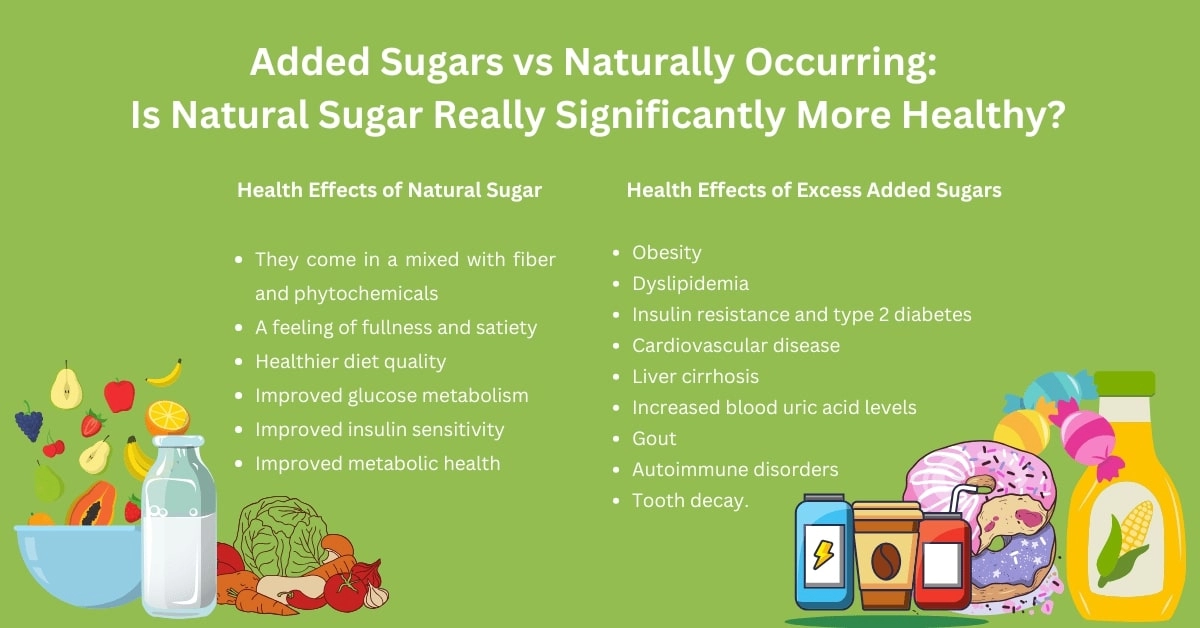

Natural or naturally occurring sugars are those naturally present in many foods and beverages (such as milk, fruits, and vegetables). In contrast, sugars are added during food processing (such as syrups and concentrated fruit or vegetable juices).

Added sugars pose no significant harm to the health if consumed in the recommended amounts (less than 10% of the daily calorie intake). However, overconsumption of added sugars leads to abdominal obesity, as excess sugars are converted into fatty acids, which may lead to a cascade of processes causing metabolic changes, low-grade systemic inflammation, and chronic diseases such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and liver cirrhosis.

In contrast, naturally occurring sugars come in a mixture with other compounds, such as dietary fiber and/or phytochemicals. They slow digestion and absorption, thus reducing blood glucose elevations after food intake while promoting satiety and fullness. Thus, they lead to lower food intake and prevent adverse effects on metabolism and health.

The sweetness of fructose and sucrose may enhance food palatability, subsequently enhance feeding behavior, and lead to overeating. Added sugars may also induce addition-like behaviors, such as binging and dependence.

Introduction

Natural or naturally occurring sugars are naturally present in many foods and beverages (such as milk, fruits, and vegetables). In contrast, added sugars are artificially added to foods during processing and preparation or at the table (such as syrups, biscuits, cakes, and soda).

Some naturally occurring sugars are fructose, glucose, sucrose, lactose, galactose, dextrose, and maltose. Added sugars include some of the same sugars added to food at some point before consumption; common added sugars are fructose, sucrose (table sugar, which is 50% fructose and 50% glucose), HFCS (high-fructose corn syrup), glucose, and dextrose (1).

The primary sources of added sugars are sugar-sweetened beverages (soda, fruit drinks, sports, and energy drinks), coffee and tea that are sweetened before sale, white bread, breakfast cereals, baked goods, desserts, biscuits, sweet snacks, and candy (1, 2).

Recommended Daily Values & Sources

The is no recommended daily value (RDV) for natural sugars, as no recommendation has been made.

According to the 2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, the RDV of carbs is 130g daily, and added sugars, if consumed, should be less than 10% of daily calorie intake. For example, an individual on a 2000-calorie diet should limit their added sugar intake to 50g (equal to 200 calories) daily.

The amount of added sugars is commonly written in the Nutrition Facts label on the packaging. Foods containing 5% of the RDV or less are considered low in added sugars, whereas foods containing 20% of the RDV are considered high (1, 3, 4).

The manufacturer's choices determine which foods contain which type of added sugar. The Nutrition Facts Labels list the amount of added sugar and, in the ingredients section, the type of added sugar. Fructose-containing sugars, such as HFCS and sucrose (table sugar), are cheaper, sweeter, and have a longer shelf life and functional properties (such as texture, color, and moisture retention) than glucose, making them more commonly used as added sugars.

HFCS is commonly found in canned foods, cereals, baked goods, desserts, soda, and flavored and sweetened dairy products. Sucrose or table sugar can be added to puddings, milkshakes, cakes, sweet sauces, cookies, pancakes, and cereals. Glucose or dextrose may be found in infant formulas, dried fruits, energy drinks, and sauces.

Health Effects of Naturally Occurring Sugars

Fruits, berries, vegetables, and natural honey contain naturally occurring or intrinsic sugars, as well as high amounts of other compounds, such as dietary fiber and/or phytochemicals, with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic, and health-promoting properties.

This complex mixture of nutrients in fruits, vegetables, and their juices has been shown to slow digestion and absorption, reducing blood glucose elevations after food intake while promoting satiety and fullness. Thus, it leads to lower food intake and prevents adverse effects on metabolism and health.

Studies have also shown that naturally occurring sugar intake is associated with higher dietary fiber and unsaturated or healthy fat intake and overall healthier diet quality than added sugar intake (5, 6).

The daily intake of carbohydrates should be kept within the recommended range (i.e., 130g daily) to avoid adverse effects on health caused by excess sugar.

What About Foods With High Levels of Natural Sugars?

One of the widely consumed foods with naturally high levels of sugar is honey. Honey is an added sugar and should be consumed within the recommended amounts, but unlike table sugar and HFCS, it has a different nutritional profile and health impact.

For example, honey contains 82% sugars, mainly fructose (50%) and glucose (44%), only 0.2g of dietary fiber, and is rich in phytochemicals (phytonutrients) such as polyphenols and organic acids. Despite its high sugar content, honey has a medium glycemic index of 61.

Due to its large amounts of polyphenols, which have anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti-obesity, hypotensive, blood sugar, and fat-lowering effects, honey may reverse adverse metabolic changes, improve insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism, and prevent high blood pressure and coronary artery disease. Polyphenols in honey may also limit weight gain and fat tissue formation (7).

Health Effects of Added Sugars

Most studies show that the pathological changes mentioned below are attributed to high amounts of added fructose and fructose-containing sugars, not glucose (8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13).

Added glucose is not harmless either; it also induces obesity and may lead to metabolic disturbances. However, due to their different metabolic pathways (fructose is almost entirely metabolized in the liver) and regulatory mechanisms, high amounts of fructose may lead to significantly more adverse effects than other types of sugars.

Metabolic Changes

According to studies, excess added fructose intake leads to unregulated uptake and metabolism of fructose in the liver, catalyzed by fructokinase C, an enzyme not regulated by energy status. This leads to de novo lipogenesis and activation of the transcription factors ChREBP and SREBP1c and their coactivator PPARγ coactivator 1β, linked to the gene expression of enzymes contributing to carbohydrate metabolism. The changes increase the lipid (fat) supply to the liver by synthesizing fatty acids, inhibiting their oxidation, and promoting the synthesis and secretion of VLDL cholesterol, leading to increased triglycerides and LDL or “bad” cholesterol in the blood (8, 9, 10, 11).

Increased fat levels in the liver promote local or hepatic insulin resistance, leading to molecular changes in the insulin receptor and impaired insulin action (8).

Local or selective insulin resistance activates de novo lipogenesis even more strongly, creating a vicious cycle in which VLDL cholesterol synthesis and secretion are further exacerbated, triglycerides are elevated, fats are accumulated in tissues, and insulin signaling is further impaired, leading to insulin resistance in the whole body (8).

Moreover, fructose metabolism leads to adenosine triphosphate (ATP) conversion to adenosine monophosphate (AMP) and depletion of inorganic phosphate, leading to uric acid production, another risk factor of fatty liver and metabolic syndrome (8).

An indirect pathway contributing to the development of metabolic changes includes increased energy intake and positive energy balance, which lead to fat gain and obesity and subsequently dysregulated fat and carbohydrate metabolism. Obesity promotes low-grade chronic inflammation in the body and increases the risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease (12).

In summary, excess added fructose in the diet leads to fructose conversion into fatty acids, causing a cascade of processes that leads to increased fat levels in the liver, increased triglycerides and LDL or “bad” cholesterol in the blood, and insulin resistance in the liver, which may further advance to insulin resistance in the whole body, leading to the development of liver disease of different stages, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

Dysbiosis & Neuroinflammation

Dysbiosis, or the disruption of the normal gut microbiota, increases the risk of pathological metabolic changes. Diets high in added sugars may reduce probiotic or good bacteria, impair intestinal wall permeability and mucosa, disrupt tight junctions, and increase bacterial translocations, causing increased signaling of inflammatory proteins or cytokines.

According to a study, fructose, but not glucose, may decrease the levels of several microbes with anti-inflammatory properties, such as Eubacterium eligens and Streptococcus thermophilus.

Additionally, the pathological changes in the gut may enable the entry of endotoxins into the bloodstream, leading to excessive production of proinflammatory cytokines (13).

Animal studies note that dysbiosis may also contribute to the inflammatory changes of the hippocampus and loss of nerve cells, highlighting a potential mechanism for the neurological and cognitive impairments linked with sugar and obesity (13).

In summary, high levels of added fructose lead to pathological changes in gut microbiota and damage to the intestinal wall. This promotes local inflammation and enables the entry of toxins into the bloodstream, causing low-grade inflammation in the body and increasing the risk of nerve cell damage.

The Addictive Effects of Added Sugars

The sweetness of fructose and sucrose may enhance food palatability, subsequently enhance feeding behavior, and lead to overeating. Added sugars may also stimulate dopaminergic pathways in the brain and induce addition-like behaviors, such as binging and dependence.

High-fructose diets may induce leptin resistance and decrease leptin excursions, thus increasing the risk of overeating and obesity (9). In healthy humans, leptin regulates food intake and energy use balance.

Interestingly, fructose and glucose affect hypothalamic blood flow and cerebral cortex reactivity to food differently, leading to different effects on feeding behavior. FGF21 is a hormone regulating macronutrient homeostasis and selection; its increased levels are linked to chronic diseases. Fructose causes acute and robust increases in circulating FGF21, whereas glucose has less substantial and delayed effects on hormone levels (9). Data from animal studies suggests that elevated levels of FGF21 could signal the brain to reduce further sugar consumption.

Studies have shown that high-fructose diets may lead to spontaneous reductions in other sugar consumption, highlighting the regulatory mechanisms of sugar consumption (9).

In summary, fructose and glucose affect the brain differently. A high intake of added fructose may affect normal eating behavior and lead to overeating, binging, and dependence.

Potential Health Risks of Added Sugars

However, diets high in added sugars, primarily fructose and fructose-containing sugars, may significantly increase the risk of the following conditions (3, 8, 9, 10, 14, 10):

- Changes in eating behavior and obesity

- Dyslipidemia or abnormal blood fat levels

- Insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes

- Cardiovascular disease and stroke

- From fatty liver (MASLD) to liver cirrhosis and liver cancer

- Increased blood uric acid levels

- Gout

- Decreased executive function

- Increased risk of autoimmune disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis (MS), psoriasis, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis.

- Tooth decay. It occurs when oral bacteria metabolize sugars and produce acid, which harms the tooth enamel and dentine and causes caries.

Chronic diseases associated with increased added sugar intake are independent of body weight gain or total energy intake (3).

Added sugars pose no significant harm to the health if consumed in the recommended amounts (less than 10% of the daily calorie intake).

Sources

- https://www.fda.gov/food/nutrition-facts-label/added-sugars-nutrition-facts-label

- https://www.cdc.gov/healthy-weight-growth/be-sugar-smart/index.html

- https://www.uptodate.com/contents/healthy-diet-in-adults

- https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8468124/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5465852/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7913905

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4822166/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5785258

- https://joe.bioscientifica.com/view/journals/joe/257/2/JOE-22-0270.xml

- https://www.journal-of-hepatology.eu/article/S0168-8278(21)00161-6/fulltext

- https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2022.988481/full

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9966020/

- https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/sugars-and-dental-caries