Choline — Rich Foods, Supplements, Health Benefits, and Functions

Introduction

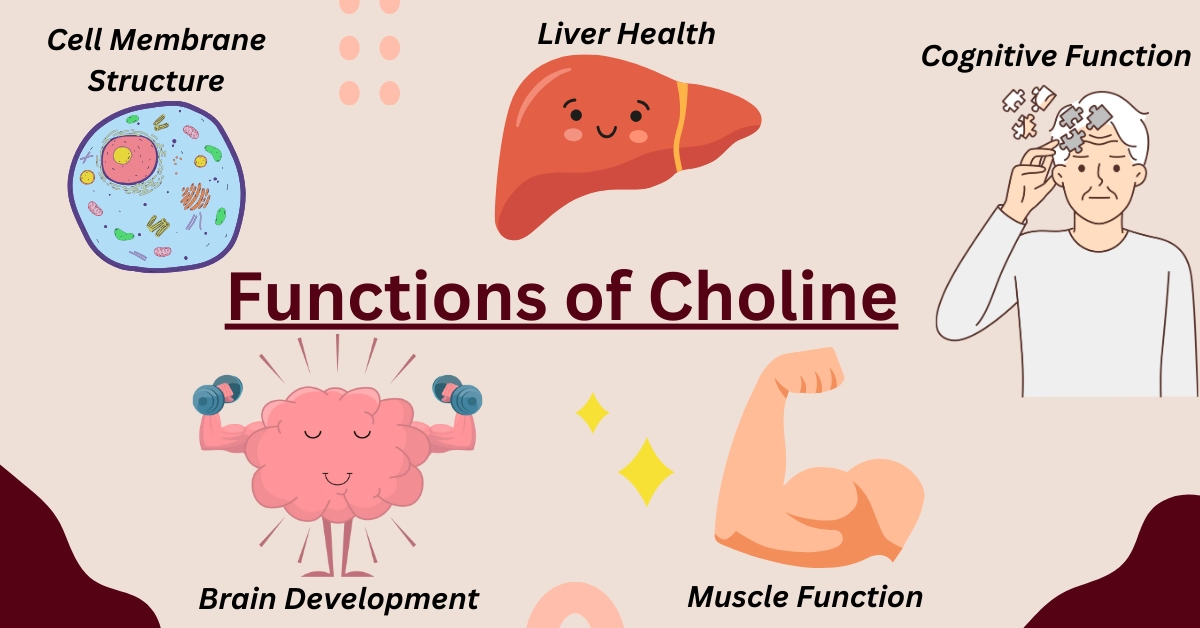

Choline is an essential nutrient in a classification all on its own. It is neither a mineral nor a vitamin. Often overlooked, this essential nutrient plays a critical role in various bodily functions, from brain development and muscle function to liver health.

In this article, we will explain choline in-depth: what it is, what it does, and how it affects our health.

Содержание

What is Choline?

Choline is a water-soluble essential nutrient with an amino acid-like structure. Due to its structural and functional similarities, it was once grouped with B vitamins; however, choline is not classified as a vitamin.

Choline has a basic structure with a nitrogen atom connected to three methyl groups (CH3) and an alcohol group (OH).

These methyl (CH3) groups are essential for choline's physiological role. Choline is a source of methyl groups essential for various metabolic processes, such as turning homocysteine into methionine. It is necessary for the synthesis of phosphatidylcholine and sphingomyelin, crucial phospholipids vital for the structure of cell membranes (1).

In addition to other functions, choline plays a main role in the synthesis of acetylcholine, a vital neurotransmitter involved in memory, mood regulation, muscle control, and various other functions within the brain and nervous system.

History of Choline

The history of choline traces back to 1850, when Theodore Gobley discovered a substance in egg yolks, which he named lecithin, after the Greek word for egg yolk. After a few years, in 1862, the German chemist Adolph Strecker discovered choline as a component of bile. Some years later, a similar compound was found in the brain and named “neurine.” In time, the latter two compounds were found to be the same molecule, while lecithin was identified as a chemical derivative of choline (2).

The importance of choline in human nutrition and health gradually became recognized over the years. In 1998, the Institute of Medicine officially recognized choline as an essential nutrient. Since then, research has continued to uncover its vital role in various physiological processes, leading to its inclusion in dietary guidelines and recommendations worldwide.

Absorption, Metabolism, and Normal Range

Choline found in the diet exists in various forms, including free choline and esters like phosphocholine, glycerophosphocholine, sphingomyelin, or phosphatidylcholine. When consumed, these choline esters are broken down by pancreatic enzymes, releasing choline. The small intestine absorbs dietary choline, facilitated by choline transporters (3).

Choline that is not bound to other molecules enters the bloodstream through the portal circulation and is primarily taken up by the liver. However, phosphatidylcholine and sphingomyelin, the lipid-soluble forms of choline, enter the bloodstream through the lymphatic system, avoiding initial processing by the liver (3).

Most cells of the body turn choline into the main form of choline phosphatidylcholine or lecithin.

Aside from consuming it through food, choline can also be generated through the synthesis of phosphatidylcholine from basic components. The liver is where most of the body's choline is naturally produced (3).

While choline levels are typically not routinely assessed in healthy individuals, plasma choline concentrations generally range from 7 to 20 mcmol/L in adults. Even during prolonged periods of fasting, these levels typically remain within the range of 7–9.3 mcmol/L and do not drop below 50% of normal. This could be because membrane phospholipids are broken down to sustain plasma choline levels above this minimum threshold or due to the body's own synthesis of choline (1).

When choline levels are low, the liver recycles choline and redistributes it from the kidneys, lungs, and intestines to the liver and brain (4). It also excretes choline through the bile into the gastrointestinal system.

Recommended Intakes

Various factors such as gender, menopausal status, pregnancy, lactation, and genetic variations influence an individual's choline needs. Despite the body's ability to synthesize choline, it's insufficient to meet human requirements entirely. Therefore, recommended adequate intake (AI) levels have been established at 425 mg/day for women, 450 mg/day for pregnant women, 550 mg/day for men, and lactating women (3).

Below, you can find the adequate intake levels for choline based on age and gender, according to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020-2025 (5).

| 2 to 3 | 4 to 8 | 9 to 13 | 14 to 18 | 19 and above | |

| Male | 200mg | 250mg | 375mg | 550mg | 550mg |

| Female | 200mg | 250mg | 375mg | 400mg | 425mg |

The dietary requirement for choline may be lower in premenopausal women compared to children or other adults, as estrogen stimulates the PEMT gene responsible for choline biosynthesis in the liver. However, some women have different variants of this gene that prevent estrogen from boosting their natural choline production (1, 3).

In cases of folate or vitamin B9 deficiency, which is also a methyl donor, the demand for dietary choline increases since choline becomes the primary supplier of methyl groups (1).

Foods Rich in Choline

Foods rich in choline include a diverse range of options from both animal and plant sources. Eggs, liver, red meat, poultry, and fish are notable animal-based sources, providing substantial amounts of this essential nutrient. Plant-based sources such as soybeans, broccoli, cauliflower, and certain nuts and seeds also offer significant choline content.

Below is a list of foods rich in choline according to their average serving sizes per person.

Food Name | Choline Content | Serving Size |

| Eggs (hard-boiled) | 147mg | 50g or 1 large |

| Soybeans (boiled) | 82mg | 172g or 1 cup |

| Caviar | 79mg | 16g or 1 tablespoon |

| Salmon (cooked, dry heat) | 77mg | 85g or 3 ounces |

| Chickpeas (mature seeds, boiled) | 70mg | 164g or 1 cup |

| Pork (loin, broiled) | 68mg | 85g or 3 ounces |

| Chicken (meat and skin, roasted) | 56mg | 85g or 3 ounces |

| Cauliflower (raw) | 47mg | 107g or 1 cup, chopped |

| Broccoli (raw) | 28mg | 148g or 1 NLEA serving |

| Peanut butter (smooth) | 20mg | 32g or 2 tablespoons |

If interested, you can also find a list of foods high in choline based on 100g servings.

Approximately half of the choline intake in the U.S. comes from phosphatidylcholine or lecithin, a compound found in many foods. As an emulsifier, it is frequently used as an additive in processed foods, such as salad dressings and margarine, enhancing texture and consistency. Additionally, choline is naturally present in breast milk and is commonly included in commercial infant formulas (1).

Health Benefits and Functions of Choline

Choline is an essential nutrient with numerous health benefits and vital functions in the body. It plays a crucial role in brain development and function, as it is a precursor to the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, which is involved in memory, mood regulation, muscle control, and regulating sleep-wake cycles.

Choline is necessary for maintaining the structural integrity of cell membranes and is involved in the production of compounds essential for fat metabolism, such as phospholipids and lipoproteins. Additionally, choline contributes to homocysteine reduction through being a methyl group donor.

Choline also supports liver health by aiding in the transport and metabolism of fats and cholesterol, helping to prevent fatty liver disease.

Below, we will discuss these functions in more depth based on scientific evidence.

Neurological Health and Cognitive Function

Neurological Function

Choline acetyltransferase aids in acetylcholine synthesis, while acetylcholine esterase breaks it down into choline and acetate (6).

Additionally, citicoline or CDP-choline supplementation has been shown to boost the production and release of neurotransmitters derived from tyrosine, such as noradrenaline, adrenaline, and dopamine.

Citicoline, a choline metabolite, has been used in the management of traumatic brain injury for decades. Research shows that citicoline supplementation can help reduce brain swelling and improve recovery of consciousness and neurological symptoms (7).

Cognitive Function

Various studies have found choline intake to be positively associated with improved cognitive functions, such as verbal and visual memory, learning, processing speed, sustained attention, executive function, and global cognition (6).

Neurological Disorders

Individuals with Alzheimer’s disease exhibit reduced levels of the enzyme responsible for converting choline into acetylcholine within the brain. Moreover, since phosphatidylcholine can act as a precursor to phospholipids, it contributes to maintaining the structural integrity of neurons, potentially enhancing cognitive function among older adults. Consequently, experts hypothesize that increasing phosphatidylcholine intake might mitigate the advancement of dementia in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases (1, 6).

Choline and its metabolites also play various roles in maintaining typical visual functions, including supporting the function of the retina. Citicoline, a choline metabolite, was demonstrated to improve retinal function and neural conduction along visual pathways beyond the retina. This enhancement resulted in significantly improved responses of the visual cortex to stimuli compared to a placebo. There was a trend indicating a lower rate of eye disease progression with topical citicoline use (6).

Pregnancy and Fetal Development

Research indicates that introducing choline supplements into either the maternal or child's diet during the initial 3 years of life may have several benefits: fostering typical brain development, protecting against neural and metabolic damage, especially in cases of fetal alcohol exposure, supported by animal and human evidence, and enhancing neural and cognitive performance, as suggested by animal studies (8).

Various nutritional elements have been associated with the development of neural tube defects. One of the primary factors is the intake of folic acid or vitamin B9 around the time of conception. Like folic acid, choline participates in the methylation process that converts homocysteine to methionine. Some studies suggest that both choline and methionine intake could play a role in decreasing the risk of neural tube defects, even independent of folate intake from both dietary sources and supplements (6, 9).

Research on children's neurological and cognitive development is inconclusive. One study did not correlate maternal choline supplementation during pregnancy with cognitive performance in children at 3 years old (10). Conversely, another study found maternal choline intake was significantly associated with increased visual memory in 7-year-old children (11).

Cardiovascular Health

Certain studies propose that choline could benefit cardiovascular health by lowering blood pressure, positively affecting lipid profile, and reducing plasma homocysteine levels (12).

Conversely, other research indicates that elevated dietary choline intake might increase the risk of cardiovascular disease. This is because some choline and related dietary compounds, like carnitine, are metabolized by gut bacteria into trimethylamine (TMA), which the liver converts into trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO). High TMAO levels have been associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (1).

Fatty Liver Disease

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease or NAFLD is a condition not caused by alcohol consumption where fat builds up in the liver. NAFLD can range from simple fatty liver (steatosis) to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, which involves liver inflammation and may progress to liver cirrhosis. It's often associated with obesity, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, high cholesterol, and high triglyceride levels.

Choline deficiency is associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, as phosphatidylcholine helps carry fats out from the liver. Without enough choline, the liver can accumulate excess fat (1, 13).

The research found an inverse association between dietary choline consumption and the risk of NAFLD (14). Another research concluded postmenopausal women with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and low choline intake had a higher risk of fibrosis, but choline intake didn't affect fatty liver development (15).

Type 2 Diabetes

Elevated consumption of phosphatidylcholine was linked to a higher risk of type 2 diabetes in three studies involving both men and women. Those with the greatest intake of choline had a 34% higher risk of developing diabetes compared to those with the lowest intake. However, the precise cause behind this link remains uncertain and requires more investigation (13).

Breast Cancer

Recent research has linked high dietary choline intake to a reduced risk of breast cancer. In the initial study exploring this connection, it was found that women with high dietary choline intake experienced a 24% decrease in breast cancer risk (16). This may be due to choline’s DNA-protecting function: choline deficiency can lead to DNA damage and programmed cell death.

Choline Deficiency

Although most Americans consume less choline than the adequate intake recommendation, choline deficiency is exceedingly rare among healthy individuals, largely because the body can synthesize some choline, too (13).

While rare, a deficiency in choline can lead to muscle and liver damage, as well as fatty liver disease, as discussed above (1).

Factors putting people at a higher risk of choline deficiency include (1, 6, 13):

- Pregnancy or lactation, due to increased demand

- Vegetarian or vegan diets, due to dietary restrictions

- Cystic fibrosis, due to increased fecal losses

- Certain genetic traits, such as a PEMT gene variant that leads to reduced choline synthesis

- Total parenteral nutrition, as it usually lacks choline as a nutritional component.

Choline Supplements

Apart from obtaining choline from dietary sources, various forms of choline supplements are accessible either on their own or combined with B-complex vitamins or in multivitamin/mineral products. These supplements typically contain choline in amounts ranging from 10mg to 250mg. The forms of choline in these supplements include choline bitartrate, phosphatidylcholine, and lecithin (1).

Choline alfoscerate, also known as alpha-glycerophosphocholine (α-GPC or GPC), is a widely used cholinergic compound and precursor to acetylcholine. It's commonly utilized as a dietary supplement, favored for its high choline content (41% by weight) and capability to penetrate the blood-brain barrier.

Both preclinical and clinical studies have demonstrated that supplementation with GPC and other forms of choline can yield positive outcomes, particularly in terms of enhancing endothelial function and cognitive performance (17).

Choline Toxicity

Excessive consumption of choline can result in low blood pressure (hypotension) and liver toxicity. Additionally, it may lead to elevated levels of TMAO, which is associated with increased cardiovascular disease risk (13).

Symptoms may include profuse sweating or salivation, a fishy body odor, or nausea and vomiting.

The tolerable upper intake level for choline is the same for men and women. This value is 2000mg for people aged 9 to 13, 3000mg for ages 14 to 18, and 3500mg for people above 19 (1).

Interactions With Medications

Choline has not been associated with any clinically significant interactions with medications (1).

Summary

Choline is a water-soluble essential nutrient with an amino acid-like structure that is classified as neither a vitamin nor a mineral.

Dietary choline is absorbed in the small intestine but can also be synthesized in the body, mostly by the liver.

Recommended adequate intake levels have been established at 425 mg/day for women, 450 mg/day for pregnant women, 550 mg/day for men, and lactating women.

Foods rich in choline include eggs, red meat, poultry, fish, soy products, cruciferous vegetables, and certain types of nuts and seeds.

Choline plays a crucial role in brain development and function, as it is a precursor to the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, which is involved in memory, mood regulation, and muscle control. It is also necessary for maintaining the structural integrity of cell membranes and is involved in the production of compounds essential for fat metabolism.

Although rare, choline deficiency can lead to muscle and liver damage, as well as fatty liver disease. Conversely, choline toxicity can result in low blood pressure, liver toxicity, and increased cardiovascular risk.

References

- https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Choline-HealthProfessional

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23183298/

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/275669237

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2782876/

- https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf

- https://lpi.oregonstate.edu/mic/other-nutrients/choline

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21432836/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7352907

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2782876/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22686384/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23425631/

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282878689

- https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/choline/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25320186/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22338037/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2430758/

- https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/endocrinology/articles/10.3389/fendo.2023.1148166/full