Is Sodium Bad for You — Health Impacts, Recommended Intake, and Food Sources

Introduction

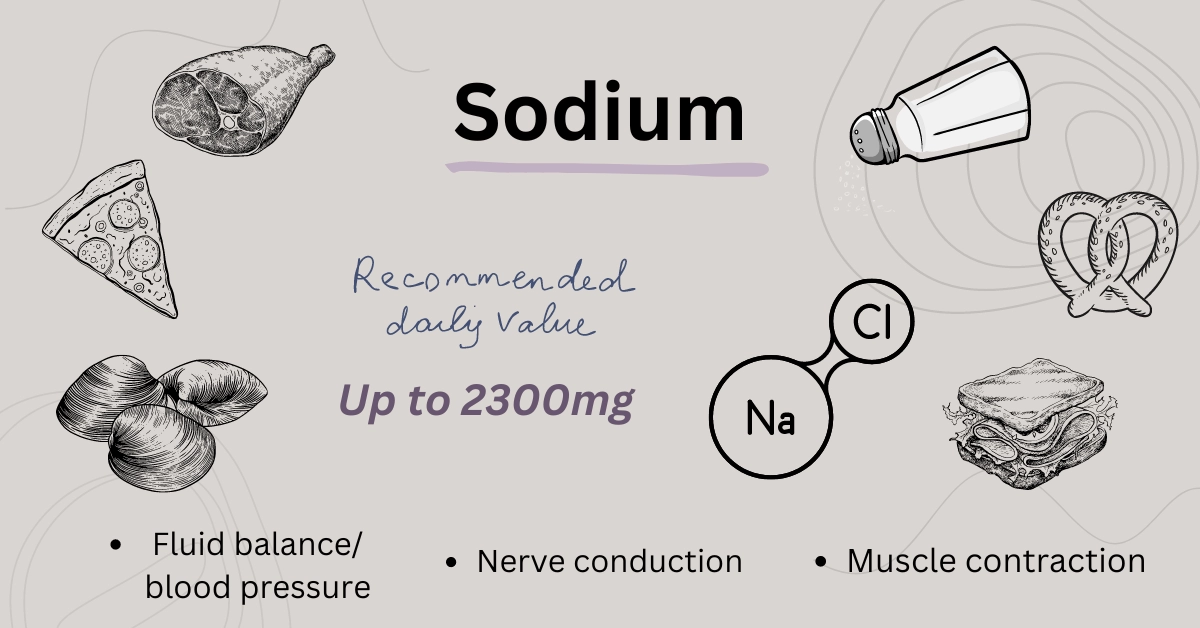

Sodium is a vital mineral that is critical in maintaining various physiological functions in the human body. As an essential electrolyte, sodium is primarily involved in basic neurological functions such as transmitting nerve impulses, regulating fluid balance, and facilitating muscle contractions. The body needs sodium to maintain proper hydration levels, support normal cell function, and ensure that nerves and muscles operate effectively.

Despite its crucial roles, excessive sodium consumption is a significant public health concern due to its association with high blood pressure.

In this article, we will discuss sodium nutrition and metabolism, as well as its function and what happens when there is not enough or too much of it.

Table of contents

- Recommended Intake

- Food Sources Of Sodium

- Absorption, Metabolism, and Regulation

- Functions in the Human Body

- Health Risks of High Dietary Sodium

- Cardiovascular Health and Blood Pressure

- Cardiovascular Health

- Endothelial Function

- Cancer

- Osteoporosis

- Kidney Stones

- Chronic Kidney Disease

- Sodium Toxicity or Hypernatremia

- Sodium Deficiency or Hyponatremia

- Interactions with Medications

- Summary

Recommended Intake

Balancing sodium intake is crucial for overall health. The daily values of nutrients are reference amounts established by health authorities, indicating the recommended daily intake to consume or not exceed each day.

According to the FDA, the daily value of sodium is up to 2300mg per day. Generally, a serving of food with 115mg (5% DV) or less sodium is considered to be low in sodium, whereas a serving with 460mg (20% DV) or more is considered to be high in sodium (1).

The recommended intake for sodium is up to 2300mg daily for ages 14 and above. This is the upper intake value to reduce the risk of chronic diseases, particularly cardiovascular and high blood pressure. These values are the same for men and women, as well as for pregnant and lactating women (2).

| 2 to 3 years | 4 to 8 years | 9 to 13 years | 14 and above |

| 1200mg | 1500mg | 1800mg | 2300mg |

Despite this, the average sodium intake in the U.S. population for individuals aged 1 and older is 3393mg per day, ranging from about 2000mg to 5000mg daily (2).

Food Sources Of Sodium

Sodium is primarily consumed in the diet in the form of salt, known chemically as sodium chloride. One average serving size of table salt, equal to 1 teaspoon or 6g, provides 2326mg of sodium.

This mineral is also naturally present in many foods, including vegetables, dairy products, meat, and seafood. However, most dietary sodium intake in modern diets comes from processed and packaged foods. Common sources of high sodium intake include canned soups, snack foods, deli meats, sauces, and fast food.

Salt is utilized in several ways as a food ingredient, including curing meat, baking, thickening, enhancing flavor, preserving freshness, and retaining moisture.

Only a small fraction of sodium intake comes from naturally occurring sodium in foods or salt added during home cooking or at the table. Most sodium consumed in the U.S. is from salt added during commercial food processing and restaurant preparation (2).

Sodium is present in nearly all sorts of food, including mixed dishes like sandwiches, burgers, and tacos, rice, pasta, and grain dishes, pizza, meat and seafood dishes, and soups. Sodium intake is closely linked to calorie intake, meaning the more food and beverages people consume, the higher their sodium intake tends to be (2).

Below, you can find a list of foods, ingredients, and dishes alike that are high in sodium according to their average serving sizes per person.

| Food Name | Sodium (Mg) | Serving Size |

| Club sandwich | 1688mg | 268g or 1 sandwich |

| Ham (roasted, extra lean) | 1023mg | 85g or 3 ounces |

| Clam (cooked) | 1022mg | 85g or 3 ounces |

| Soy sauce | 879mg | 16g or 1 tablespoon |

| Pickled cucumbers (sour) | 785mg | 65g or 1 medium |

| Pizza (pepperoni, Pizza Hut) | 664mg | 96g or 1 slice |

| Pretzel (hard, plain, salted) | 486mg | 28.35g or 3 ounces |

| Caviar | 240mg | 16g or 1 tablespoon |

| Cheddar cheese | 183mg | 28g o 1 ounce or 1 slice |

| White bread | 142mg | 29g or 1 slice |

| Mayonnaise | 88mg | 13.8g or 1 tablespoon |

| Olive (ripe, canned) | 24mg | 3.2g or 1 small |

You can also find a list of foods high in sodium based on equal 100g servings of each.

Absorption, Metabolism, and Regulation

Sodium is the primary cation found in the space outside the cells or extracellular fluid. In an adult male, the average total sodium content is 92g. About half of this sodium (46g) is in the extracellular space. Approximately 11g is found inside the cells, or intracellular fluid and about 35g is stored in the skeleton (3).

Sodium is absorbed primarily in the distal small intestine and the large intestine. The body's sodium balance, which is closely connected to water balance, is regulated by the kidneys. For healthy individuals, the amount of sodium excreted in the urine each day must nearly match the amount ingested and absorbed from the intestines. However, kidneys have a tremendous ability to adapt to significant fluctuations in sodium intake to maintain overall body sodium balance.

The endocrine system controls the balance between sodium and water. Antidiuretic hormone, which is secreted by the pituitary gland, causes the kidney to regulate water excretion, which in turn controls the osmolality of the extracellular fluid. The preservation of sodium balance is necessary for the maintenance of vascular volume. Kidney processes that control sodium retention or loss are regulated by the natriuretic hormone produced in the heart and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system or RAAS (4).

Overall, the three main hormones involved in sodium and water regulation are antidiuretic hormone, angiotensin, and aldosterone (4).

Sweat and feces both lead to small sodium losses, which rise with sodium consumption (3).

Functions in the Human Body

Maintaining proper water and sodium levels is crucial for cell function. Because cell membranes have low permeability to minerals, water moves by osmosis from areas of lower mineral concentration to areas of higher solute concentration to balance the osmotic concentrations of extracellular and intracellular fluids. Therefore, sodium is vital for regulating electrolytes and water balance (5).

As sodium is the main factor determining extracellular fluid volume, including blood volume, various physiological mechanisms that regulate blood volume and pressure operate by adjusting the body's sodium levels (6).

The other crucial role of sodium in the body relates to nerve and muscle function and maintenance of membrane potential. Working alongside potassium, sodium functions like a chemical battery that powers nerve impulses and muscle contractions. This battery is maintained by sodium-potassium pumps in cell membranes. When a nerve cell needs to communicate, it opens channels, allowing sodium to flood in, prompting the cell to fire. This triggers a chain reaction, sending signals from cell to cell until they reach the brain or muscles. In response to nerve signals, muscle cells adjust their sodium/potassium balance to contract and move the body (7).

Sodium absorption in the small intestine is crucial for the uptake of chloride, amino acids, glucose, and water. Similar processes are used to reabsorb these nutrients after they are filtered from the blood by the kidneys (6).

Health Risks of High Dietary Sodium

Excess dietary sodium is a significant public health concern due to its association with various adverse health effects. While sodium is an essential mineral necessary for maintaining normal physiological functions, excessive intake can lead to serious health problems.

The World Health Organisation considers excessive sodium consumption to be over 5g of sodium intake per day (8).

Cardiovascular Health and Blood Pressure

Extensive research has demonstrated that high sodium consumption elevates blood pressure significantly and is associated with the onset of hypertension and its cardiovascular complications. Increased salt consumption can cause the body to retain water, leading to high flow in the arteries. Conversely, reducing sodium intake can lower blood pressure and the incidence of hypertension (6, 9).

However, people's blood pressure responses to short-term changes in sodium intake vary widely. Some individuals show little or no change in blood pressure when they adjust their sodium intake and are known as "salt-resistant." Others, whose blood pressure changes significantly with sodium intake, are called "salt-sensitive." It's estimated that about 26% of people with normal blood pressure and 51% of those with high blood pressure are salt-sensitive (6).

In salt-sensitive individuals, the kidneys reabsorb more sodium and have a higher glomerular filtration rate (GFR) on a high-sodium diet compared to salt resistance. The increase in blood pressure helps the body get rid of the extra sodium and fluid. On the other hand, salt-resistant people can excrete excess sodium effectively, so consuming large amounts of sodium doesn't significantly raise their blood pressure (6).

While higher sodium intake is linked to an increased risk of heart failure and hypertension, excessively low sodium intake might not be beneficial. One research finds optimal health benefits to be typically seen with a sodium intake of around 3g daily (10). In contrast to this study, the National Institute of Health states that a daily intake of 1.5g of sodium lowers blood pressure even further than 2.3g (11).

The National Institute of Health supports the DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet as “heart-healthy.” One of the main targets of this diet is reducing daily sodium intake to less than 2.3g. Other aspects of the diet are foods high in potassium, calcium, magnesium, fiber, and protein and low in saturated and trans fats (11).

Cardiovascular Health

Chronic hypertension harms the heart, blood vessels, and kidneys, raising the risk of heart disease, stroke, and hypertensive kidney disease. Many clinical studies have found a significant link between salt intake and left ventricular hypertrophy, an abnormal thickening of the heart muscle, which is associated with higher mortality from cardiovascular disease (6).

Reduced sodium consumption is associated not only with lower blood pressure but is also linked to decreased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (6, 9).

Excessive salt intake can also have several harmful effects, including inflammation of the small blood vessels, structural changes, and functional problems, even in people with normal blood pressure (9).

However, all that said, a meta-analysis found insufficient evidence to confirm the significant effects of dietary advice and salt substitution on cardiovascular mortality in individuals with normal or high blood pressure (12).

Endothelial Function

Endothelial dysfunction is the impaired functioning of the inner lining of blood vessels. It is usually regarded as an initial step leading to atherosclerosis, a condition where fatty deposits accumulate inside arteries, restricting blood flow and leading to various cardiovascular problems.

Research finds that excessive sodium consumption can lead to endothelial dysfunction even in salt-resistant individuals with normal blood pressure. Thus, sodium reduction has significant potential to lower cardiovascular disease risk by keeping blood vessels healthy (6).

Cancer

An expert panel at the American Institute for Cancer Research concluded that excessive salt intake can damage the stomach lining, potentially increasing the risk of gastric cancer. Thus, sodium is classified as a probable cause of stomach cancer (6, 13).

High concentrations of salt may harm the cells that line the stomach, potentially increasing the risk of bacterial infections and causing genetic damage that promotes cancer, according to animal studies (6, 14).

It is advised to limit sodium intake during cancer treatment as a high intake of this mineral can contribute to water retention issues (13).

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is a condition characterized by weakened bones that are more prone to fracture due to loss of bone density and quality.

Several studies have found that high sodium consumption may harm bone health due to increased urinary excretion of calcium, particularly in older women. This effect may be exacerbated when there is also low calcium intake (6).

However, while, in theory, a diet high in salt could cause increased calcium excretion in urine, research on its impact on bone health is not conclusive. Some studies suggest that a high-salt diet might increase bone breakdown in postmenopausal women, while others have not consistently found this effect (15).

A more recent observational cohort study of postmenopausal women concluded that sodium consumption is unlikely to affect osteoporosis significantly (16).

Kidney Stones

Most kidney stones are made up of calcium oxalate or calcium phosphate. Individuals with high levels of calcium in their urine (hypercalciuria) are at a greater risk of developing kidney stones. High sodium intake can increase urinary calcium excretion, so reducing dietary sodium may lower the risk of stone formation, particularly in those with a history of kidney stones (6).

According to research, excessive sodium intake has been found to raise the risk of developing kidney stones, especially among women with the highest sodium consumption (17).

Chronic Kidney Disease

Chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease share common risk factors, with high blood pressure being a major one for both conditions.

Patients with chronic kidney disease often have increased salt sensitivity due to a diminished ability to excrete sodium, which can result in elevated blood pressure. However, despite the association between high sodium intake and high blood pressure, there is insufficient evidence to show that a strict low sodium restriction leads to better outcomes in chronic kidney disease compared to moderate sodium restriction (18, 19).

To help prevent the onset and advancement of chronic kidney disease, a moderate sodium restriction of less than 3 or 4g is recommended rather than a low one (18, 19).

Sodium Toxicity or Hypernatremia

Hypernatremia is a condition in which the blood sodium concentration is abnormally high. It is defined as a serum sodium concentration of more than 145mEq/L. It is less common than hyponatremia and is seen more often in infants and older adults (6, 20).

The human body balances sodium and water by concentrating urine through antidiuretic hormone and increasing fluid intake via a strong thirst response. These protective mechanisms against high sodium levels in the blood can be impaired in certain vulnerable groups and conditions where there is a deficiency of antidiuretic hormone or the kidneys don't respond to it properly (20).

Sodium levels in the blood can increase due to excessive water loss or insufficient water intake. Water loss can be due to burns, respiratory infections, kidney issues, diarrhea, or hypothalamic disorders. Insufficient water intake is often combined with an impaired sense of thirst (6).

Symptoms of hypernatremia due to dehydration from excessive water loss can include low blood pressure, reduced urine, and dizziness or fainting. Severe hypernatremia can lead to lethargy, irritability, altered mental status, stupor, seizures, and coma. The skin may feel doughy or velvety due to the loss of intracellular water (6, 20).

Acute brain shrinkage resulting from severe hypernatremia may cause intracranial and subarachnoid hemorrhage (6).

Patients with diabetes insipidus often experience excessive urination (polyuria) and extreme thirst (polydipsia) (20).

Sodium Deficiency or Hyponatremia

Hyponatremia is characterized by a serum sodium concentration below 135 mEq/L. This common electrolyte imbalance usually occurs when there is an excess of total body water relative to total body sodium content and rarely due to increased sodium loss (6, 21).

One survey from 1999 to 2004 found that hyponatremia affected 1.9% of the US population sample aged 18 and older. However, low sodium levels are uncommon among healthy individuals but are notably more prevalent among older adults and people with conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancer, and psychiatric disorders (6, 18, 22). This is partially due to the medications prescribed during these conditions, which will be discussed in the next section.

Hyponatremia is also common in hospitalized patients. Approximately 15 to 30% of hospitalized patients experience mild hyponatremia, and up to 7% have moderate-to-severe hyponatremia (23).

There are three types of hyponatremia depending on the total body sodium and total body water ratio: hypervolemic, hypovolemic, and euvolemic (21).

- Hypovolemic hyponatremia: This type occurs when both sodium and water levels are low in the body, but sodium loss is greater than water loss. Common causes include severe vomiting, diarrhea, excessive sweating, diuretic use, and conditions such as pancreatitis, hypoalbuminemia, small bowel obstruction, and certain kidney diseases.

- Euvolemic hyponatremia: Here, the total body water stays the same while sodium levels decrease, leading to diluted sodium in the blood. It can be caused by conditions such as syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH), certain medications, or hormone imbalances (Addison’s disease, hypothyroidism).

- Hypervolemic hyponatremia: This type happens when both sodium and water levels are high, but the water gain is more significant, diluting the sodium in the blood. It is often associated with conditions like heart failure and kidney disease.

The symptoms of hyponatremia depend on the level of sodium and how quickly it drops. In mild-to-moderate hyponatremia, or when sodium levels decrease gradually, patients typically experience minimal symptoms. Conversely, severe hyponatremia or a rapid drop in sodium levels can lead to a wide range of symptoms.

Symptoms of mild to moderate hyponatremia include anorexia, headache, nausea, vomiting, muscle cramps, fatigue, disorientation, and fainting. Severe and rapidly developing hyponatremia can lead to serious complications such as altered mental status, agitation, brain swelling, seizures, coma, and brain damage.

Interactions with Medications

A list of different medications can lead to decreased levels of sodium through various mechanisms, leading to an increased risk of hyponatremia. These drugs include the following (6, 21, 24):

- Diuretics (Hydrochlorothiazide, Furosemide or Lasix)

- Serotonin-reuptake inhibitors or SSRIs (Fluoxetine or Prozac, Paroxetine or Paxil)

- Tricyclic antidepressants (Amitriptyline or Elavil)

- Antipsychotics (Phenothiazine, Haloperidol)

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or NSAIDs (Ibuprofen or Advil, Naproxen)

- Antiepileptics (Carbamazepine, Valproic acid)

- Opiates (Codeine, Morphine)

- Proton pump inhibitors or PPIs (Omeprazole, Esomeprazole)

- Antineoplastics (Vincristine, Cyclophosphamide)

- Antidiabetics (Chloropropamide, Tolbudamide)

- Psychedelics (MDMA)

Sodium bicarbonate is the chemical name for baking soda. Sodium bicarbonate tablets are used as a quick-acting antacid to treat heartburn and indigestion, as well as a way to treat metabolic acidosis and prevent kidney stone formation.

However, oral use of sodium bicarbonate may limit the absorption and increase the excretion of drugs, such as Cefpodoxime (antibiotic) and Chlorpropamide (antidiabetic). Intravenous use of sodium bicarbonate may also diminish the effect of Aspirin (6).

Summary

As an essential electrolyte, sodium is primarily involved in basic neurological functions such as transmitting nerve impulses, regulating fluid balance, and facilitating muscle contractions. The body needs sodium to maintain proper hydration levels and support normal cell function.

The recommended sodium intake is up to 2300mg daily for people aged 14 and above. This is the upper intake value to reduce the risk of chronic diseases, particularly cardiovascular and high blood pressure. These values are the same for men and women, as well as for pregnant and lactating women.

Only a small fraction of sodium intake comes from naturally occurring sodium in foods or salt added during home cooking or at the table. Most sodium consumed in the U.S. is from salt added during commercial food processing and restaurant preparation.

Sodium intake is closely linked to calorie intake, meaning the more food and beverages people consume, the higher their sodium intake tends to be.

Extensive research has demonstrated that high sodium consumption elevates blood pressure significantly and is associated with the onset of hypertension and its cardiovascular complications. Conversely, reducing sodium intake can lower blood pressure and complication incidence.

Sodium is classified as a probable cause of stomach cancer, as excessive salt intake can damage the stomach lining, potentially increasing the risk of cancer.

Excess or deficient sodium levels both cause problems accordingly; however, healthy bodies have mechanisms in place to normalize sodium levels, while certain conditions and medications can predispose to sodium toxicity (hypernatremia) or sodium deficiency (hyponatremia).

References

- https://www.fda.gov/food/nutrition-education-resources-materials/sodium-your-diet

- https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3951800/

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/288226165

- https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/15/2/395

- https://lpi.oregonstate.edu/mic/minerals/sodium

- https://biobeat.nigms.nih.gov/2020/11/pass-the-salt-sodiums-role-in-nerve-signaling-and-stress-on-blood-vessels/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23658998/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6770596/

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2023.1263554/full

- https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/education/dash-eating-plan

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6483405/

- https://llsnutrition.org/sodium-salt-intake-and-cancer

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3676043/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6140170/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4880174/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4165387/

- https://nutritionsource.hsph.harvard.edu/salt-and-sodium/

- https://academic.oup.com/ajh/article/27/10/1277/2743119

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441960/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470386/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3933395/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16141458/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8747252/